Jews and the Atlantic Slave Trade

Analysis of the Jewish involvement in the Transatlantic slave trade

The topic of Jewish involvement in the Atlantic slave trade remains a contentious and often avoided subject within the academic community. The very mention of this issue can provoke accusations of antisemitism, creating a significant barrier to open and objective historical inquiry. This article seeks to address this issue by presenting a comprehensive examination of Jewish participation in the transatlantic slave trade, relying predominantly on scholarly sources authored by Jewish historians and academics.

North America

Rhode Island

Rhode Island was undoubtedly the center of the transatlantic slave trade, having more slaves per capita than any other New England state. Newport's Jewish community goes back to 1658, with another influx arriving in 1694 aboard a ship with “a number of Jewish families of wealth and respectability on board”1 who settled there, presumably from the Jewish fortress of Curaçao.2

Two Jewish individuals, Aaron Lopez and his partner, Jacob Rodriguez Rivera, owned the most successful slaving business in the state. They were of Sephardic origin.3 All 22 Newport distilleries that served the triangle slave trade were Jewish-owned.4 Even the synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, was built by African slaves.5 Nearly all Jews in Newport “had Negro domestic slaves.... the 1774 Census shows only two Newport Jewish families without slaves.”6

New York

Jewish merchants in New York largely traded agricultural products for rum, slaves, and manufactured goods.7 They engaged in trade with fellow Jews in Barbados, Curaçao, Saint Thomas, Surinam, and Jamaica, which were New York's key trade connections beyond England. Notably, Jewish communities had already been established in these ports, giving Jewish businessmen in New York a significant advantage in the West Indian trade over their competitors.8 Jewish historian Peter Wiernik directly asserted that this trade “was principally in the hands of Jews”.9

Stanley Feldstein describes something similar:

“America’s Jewish merchants, using their religio-commercial connections, enjoyed a competitive advantage over many non-Jews engaged in that same lucrative intercolonial trade. Since the West Indian trade was a necessity to America’s economy and since this trade was, in varying degrees, controlled by Jewish mercantile houses, American Jewry was influential in the commercial destiny of Britain’s overseas empire.”10

In 1717 and 1721, two ships, the “Crown” and the “New York Postillion”, which were owned by Jewish businessman Nathan Simson, arrived at the northern harbor with a total of 217 slaves. These shipments arrived directly from the African shore and were marked as “two of the largest slave cargoes to be brought into New York in the first half of the eighteenth century”.11

On several occasions, Jewish merchants in New York were found guilty of selling mentally impaired and unhealthy slaves that they had falsely claimed to be fit and healthy.12 In 1741, slaves owned by the Gomez family, often described as the “heads of the Jewish community”,13 were implicated in a suspected riot and insurrection.14

Sampson Simson, recognized as one of the leading figures in the New York Chamber of Commerce and a key contributor to its constitution, was the most prominent Jewish trader in New York between 1757-1773. He owned several ships involved in trade with both the East and West Indies.15

Virginia

Numerous Jews immigrated to Virginia and integrated into the plantation economy. Elias Legardo arrived on the ship “Abigail” in 1621, while Joseph Mosse and Rebecca Isaacke arrived on the “Elizabeth” in 1624. Manuel Rodrigues owned a plantation in Lancaster County by 1652, and David Da Costa was exporting tobacco from his plantation by 1658.16

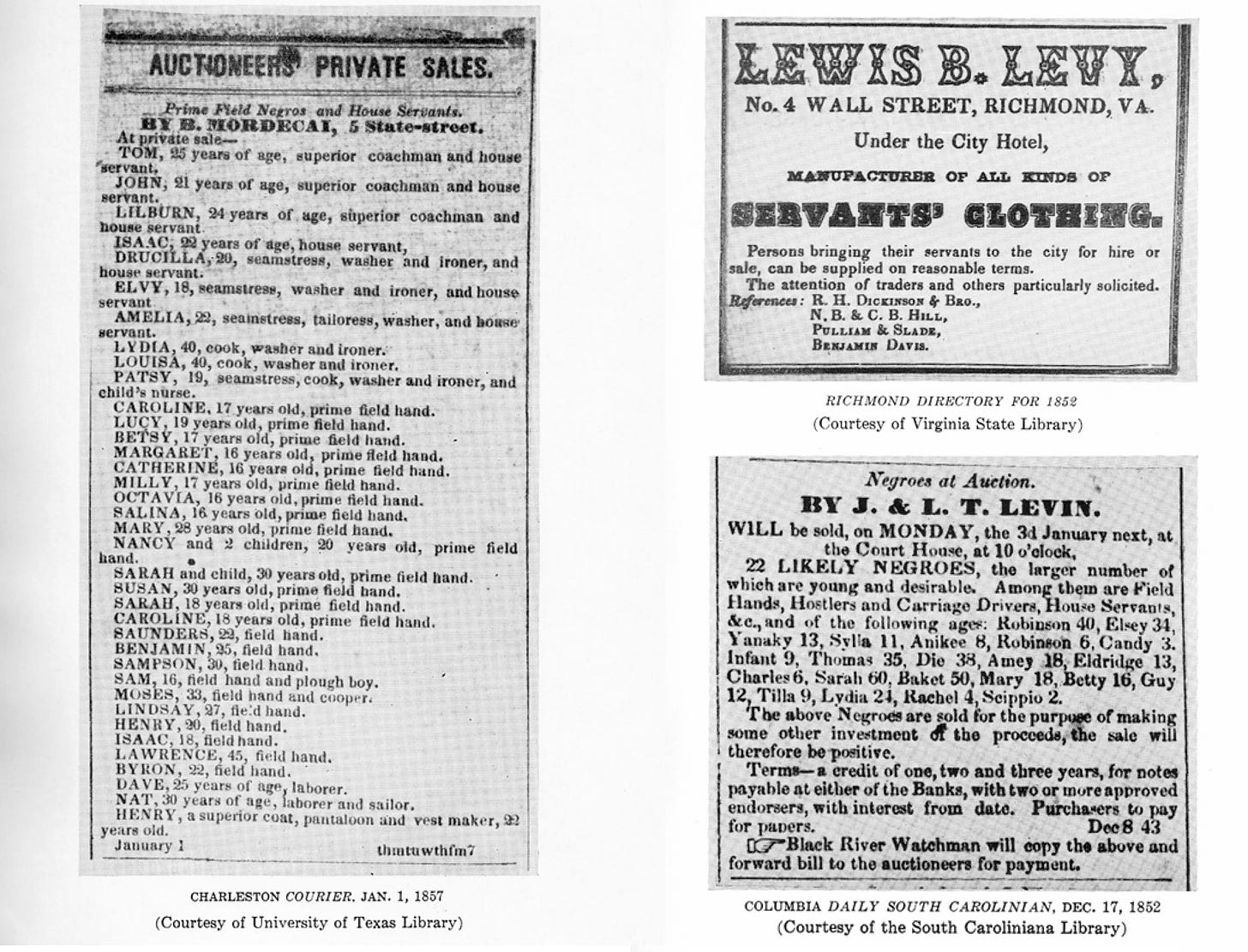

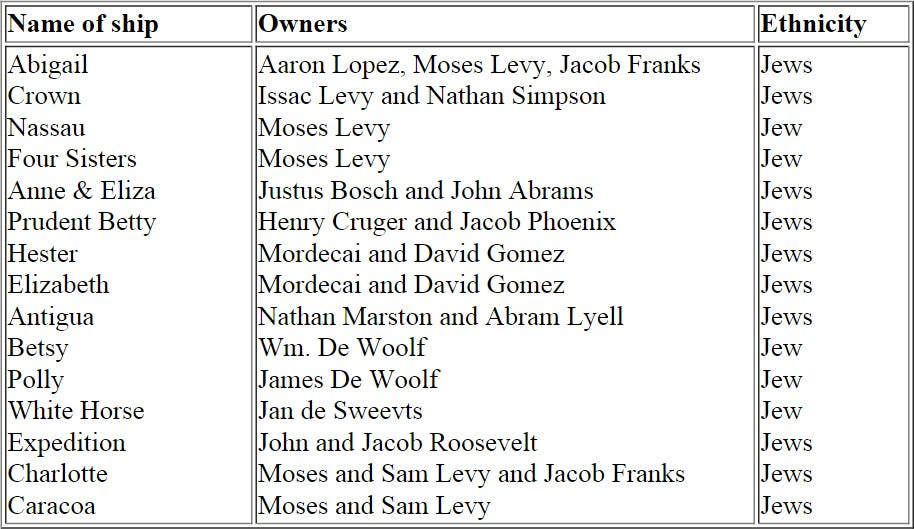

The two previously mentioned vessels, “Abigail” and “Elizabeth” are among the most well-known slave ships. The following image is extracted from the four-volume series titled “Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America” by historian Elizabeth Donnan, and it documents the Jewish-owned ships that played a significant role in the Atlantic slave trade:

The founders of Richmond's Jewish community included prominent individuals such as Samuel Myers, Solomon Jacobs, Israel and Jacob I. Cohen, Jacob Modecai, Joseph Marx and Manuel Judah, all of whom were slaveholders.17 In the post-Revolutionary era, Richmond had a population of 2,000, with half being slaves.18 By 1788, Jews constituted 17% of the “white population,” and all but one Jewish household owned “a domestic servant (a slave); one of them had three.”19 Historian Myron Berman affirms in his “Richmond’s Jewry 1769-1976” book that “Most of the Jews of Richmond in the early 19th century possessed slaves.”20

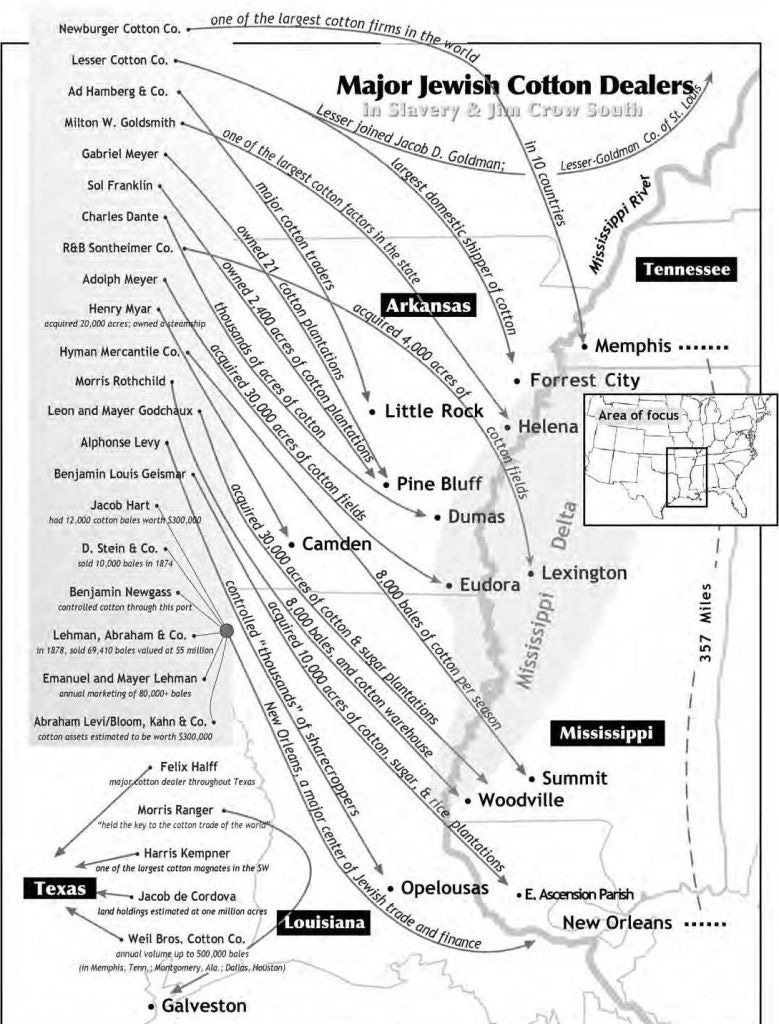

South Carolina

In 1826, the total value of slaves in the South was approximately 300 million dollars, with about one-fifth belonging to residents of South Carolina. The demand for slaves had increased so significantly that by 1860, a slave's value was seven to ten times higher than at the end of the Revolutionary War.21 Charleston, South Carolina, was home to “the most cultured and wealthiest Jewish community in America.”22 The Jewish community in Charleston flourished initially due to a thriving business in slaves. This city was once one of the great centers of Jewish commerce, which saw a decline only after the emancipation of slaves.23

Georgia

In 1733, a group of Jewish immigrants arrived in Georgia from London as land grants were being distributed.24 Georgia was the first colony to explicitly prohibit slavery, a policy that significantly impacted its settlement. Similar to the Caribbean, the settlers soon felt they could not sustain their livelihoods without black slaves,25 and they petitioned the English trustees for “the right to use Negro labor.” With Jews now making up over a third of the population, they sought permission from the Gentile colonists to be allowed to sign the petition. However, the Gentiles refused, stating that it was not appropriate for Jews to join them. The trustees' refusal to grant the petition led to a mass exodus from the colony.26

Due to the slave prohibition, only three Jewish families remained in Georgia by 1740.27 They left, as noted by Jacob Rader Marcus, “for the same reasons the others did: Negro slavery was prohibited and the liquor traffic was forbidden.”28 The Earl of Egmont documented in his diary of 1741 that all the Jews were gone from Savannah, Georgia.29

In October of 1741, the “Trustees’ Journal” reported that:

“There are various reports that negroes had at last been allowed in the Colony, upon which the Jews and...others were preparing to return to the Colony.”30

It was not until 1749, with the “model colony...falling apart”, that the trustees allowed both slavery and the use of hard liquor,31 leading to a significant economic upturn.32 By 1771, black slaves constituted half of Georgia's 30,000 inhabitants.33

USA

In 1860, the peak of slavery, the total free population of the United States and its territories was 27,489,561. A total of 393,975 people owned 3,953,760 slaves.3435 That's just 1.4% of the total population that owned slaves. 40% of Jews in the US owned slaves.36 Other sources have it MUCH higher (60%+). There were 200,000 Jews in the US in 1860.37 40% of 200,000 = 80,000. So around 80,000 Jews owned slaves. 393,975 - 80,000 = 313,975 non-Jews owned slaves.

Thus, at a minimum, well over 20% of all US slave owners were jews, despite being statistically insignificant 0.7% of the population at the time. The actual percentage was likely much higher.

South America & Caribbean

Brazil

Portuguese Jews landed in Brazil in 1503, led by the explorers Fernando de Norohha and Gaspar da Gama, who had secured a near-monopoly on settlement in the area from the Portuguese king. Bringing with them sugar cane, technical expertise, and slaves, they swiftly turned Brazil into the “most important area of sugar production in the world.” This industry became so vital that some scholars argue Portugal's survival as an independent nation depended on the Brazilian sugar trade.38

Many of those condemned as sinners sought refuge in Brazil’s open range,39 while the Jewish settlers quickly recognized the region's commercial potential, establishing up to 200 settlements along the Brazilian coastline during the 16th century.40 Jews quickly became the dominant class with a significant number of Brazil's wealthiest merchants belonging to the Jewish community.41 The Jewish sugar planters prospered on enormous plantations, relying heavily on native Indian labor and imported slaves.42 By 1600, Jewish settlers controlled the plantations, the bulk of the slave trade, over one hundred sugar mills with at least 10,000 Africans, and most of the exports of processed sugar.43

Brazil was the largest single destination for enslaved Africans, receiving about 40% of the total number of Africans transported during the transatlantic slave trade. Jewish scholar Dr. Arnold Wiznitzer described the early Jewish presence there:

“Besides their important position in the sugar industry and in tax farming, they dominated the slave trade...The buyers who appeared at the auctions were almost always Jews, and because of this lack of competitors they could buy slaves at low prices”.44

Rabbi Marc Lee Raphael, a well-respected American Jewish historian and university professor of Judaic studies, wrote in his “Jews and Judaism in the United States: A documentary history” book:

“The bylaws of the Recife and Mauricia congregations (1648) included an imposta (Jewish tax) of five soldos for each Negro slave a Brazilian Jew purchased from the West Indies Company. Slave auctions were postponed if they fell on a Jewish holiday. In Curaçao in the seventeenth century, as well as in the British colonies of Barbados and Jamaica in the eighteenth century, Jewish merchants played a major role in the slave trade. In fact, in all the American colonies, whether French (Martinique), British, or Dutch, Jewish merchants frequently dominated.”45

The economic activities of the Jews, especially in Dutch Brazil, ran the gamut of all the economic activities of the colonial era. The Sephardim were tax farmers, agriculturists, and plantation owners. The Ashkenazim participated in the commercial fields. Sixty-six Christian merchants complained to the Estates-General in 1641 that the Jews controlled the sugar trade and gave all the best positions to their newly arrived co-religionists. Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco. Owners of sugar plantations and mills were known as “Senhores de engenho”.46

In “Voyage of Francis Pyrard”, the author returns to Portugal from Bahia in 1611 and describes a fellow passenger:

“The Jew had more than 100,000 crowns worth of merchandise, most of it his own; the rest put in his care by the principal merchant and others. There was also another Jew on board as rich as he, and four or five other Jewish merchants. The profits they make after being nine or ten years in those lands are marvelous, for they all come back rich; many of these new Christians, Jew by race, but baptized being worth 60, 80, or even 100 thousand crowns…”47

These “new Christians, Jews by race” were the so-called “Marranos”, who were crypto-Jews forcibly converted to Christianity but who secretly continued to meet in the synagogue, celebrate feast days, and observe the Jewish Sabbath. The Marranos were also called conversos (the converted), neofiti (the neophytes), or “New Christians”.

Jewish historian Dr. Cecil Roth wrote that the slave revolts in parts of South America “were largely directed against [Jews], as being the greatest slave-holders of the region”.48 The Jews were expelled from Brazil in 1654, when the Portuguese reclaimed control of the Dutch colony of Pernambuco.

Curaçao

In 1634, Curaçao, a South Caribbean island, was explored and subsequently conquered by an expedition from the Dutch West India Company, which included Samuel Coheno, a Jewish interpreter. Coheno later became the island's first governor, and Curaçao earned the distinction of being referred to as “the mother of American Jewish communities.”49 Curaçao is also notable for being home to the oldest active Jewish congregation in the Americas, established in 1651. The island's synagogue, completed in 1732 on the site of an earlier one, remains the oldest continuously used synagogue in the Americas. During this period, Sephardic Jews in Curaçao and Suriname outnumbered the Dutch settlers.5051

Jewish scholars Isaac and Susan Emmanuel reported that in Curaçao, which was a major slave-trading depot, “the shipping business was mainly a Jewish enterprise”.52 Jewish slave entrepreneurs played a pivotal role as intermediaries, managing the transportation of enslaved people from Curaçao to Spanish American ports. This involvement was a natural extension of their economic activities, as Jewish settlers owned approximately 80 percent of the plantations on Curaçao.53

Jonathan Schorsch, a university professor of the Jewish Studies Program in Berlin, wrote in his famous “Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World” book:

“Jewish merchants routinely possessed enormous numbers of slaves temporarily before selling them off.”54

Barbados

A comparable situation to that observed in Curaçao was also present on the island of Barbados. The English first established a presence on the island of Barbados in 1625. Approximately twenty years later, a significant number of Jewish settlers began to inhabit the island, with steady immigration thereafter as a result of regional political events.55 It is widely believed that Jewish settlers were among the earliest colonists and pioneers of sugar cultivation in the Caribbean.56 Where sugar plantations were established, the use of enslaved labor became prevalent, and Jewish merchants played a dominant role in this market.

“With the aid of Dutch and Sephardic Jewish capital and credit, Barbados became the first British possession in the Caribbean to cultivate sugar on a large scale, and during the 1640s its economy began to be based on plantation production and slave labor.”57

Barbados, in particular, was a hub for extensive illicit trade and smuggling. According to a study by Stephen Fortune:

“Between 1660 and 1668, when the illegal trade of the island was least restricted and quite remunerative, Jewish traders became more prominent in Barbados.”58

In 1679, the citizens of Barbados sought to restrict Jewish involvement in the African slave trade. At that time, Jews constituted 22% of the nearly 20,000 white residents59 while the enslaved population approached 40,000.60 In response, the Barbadian Assembly passed an “Act restraining the Jews from keeping or trading with negroes.”61

Jamaica

Following their expulsion from Brazil in 1654, many Jewish merchants relocated to Jamaica, where they continued to expand their commercial enterprises.62 However, their trading activities soon became a source of concern for the Jamaican government. This tension is evident in a letter found in the island's archives, dated January 28, 1691, from the president and the Council of Jamaica to the Lords of Trade and Plantations, which highlights these concerns:

“The Jews eat us and our children out of all trade, the reasons for naturalising them not having been observed; for there has been no regard had to their settling and planting as the law intended and directed. We did not want them at Port Royal, a place populous and strong without them; and though told that the whole country lay open to them they have made Port Royal their Goshen, and will do nothing but trade. When the Assembly tries to tax them more heavily than Christians, who are subject to Public duties from which they are exempt, they contrive to evade it by special favours. This is a great and growing evil and had we not warning from other Colonies we should see our streets filled and the ships hither crowded with them. This means taking our children’s bread and giving it to Jews.”63

Martinique

In 1655, Benjamin D’Acosta established the first major plantation and sugar refinery in Martinique after migrating from Brazil with 900 fellow Jews and 1,100 slaves.64 According to Professor Jacob Rader Marcus, these Jewish settlers “fled to Martinique where they furthered the sugar industry and the Negro slave economy which it created.”65 The DePas family, in particular, received notable attention from the French tax authorities, who reported that the family controlled at least ten estates, each employing hundreds of slaves and servants.66 By 1680, it was documented that every Jewish household in Martinique owned at least one slave, with some households possessing ten or more. Among these, one household owned 21 slaves, while another owned as many as 30.67

Nevis

The Jewish community on the island of Nevis, primarily composed of Portuguese Jews, was also prosperous.68 These settlers arrived around 1670, having left Barbados due to high taxation.69 According to the 1707 census, all Jewish residents on Nevis were slave owners, including prominent figures like Abraham Bueno DeMezqueto (Mesquita) and Solomon Israel. The Jewish population on Nevis began to decline after the emancipation of slaves in 1838, which prompted the departure of most remaining Jewish residents.70

Saint Domingue

The Saint Dominigue revolt (Haitian Revolution) caused many settlers to seek permanent refuge in other regions, including North America. In 1793, Jewish families like the Moline were forced to leave Saint-Domingue, bringing with them African captives, branded with the Moline name, to work in Pennsylvania.71 The Gradis family, who owned significant land and operated a major shipping business on the island, was also affected by the upheaval. Abraham Gradis even conceived a plan to develop the state of Louisiana with an influx of 10,000 slaves, though this plan was never realized. Despite the harsh conditions under which enslaved Africans were held, the Jewish historian Jacob Marcus depicted Jews as the victims. Marcus complained that anti-Jewish prejudice was not absent on Saint Dominique even among the Negroes, after a slave repeated a Jewish slur he had obviously heard from his Gentile owner.72

Surinam

Jewish settlers arrived in Surinam between 1639 and 1654, bringing with them many slaves. Joseph Nunez de Fonseca, also known as David Nassi, led the last influx, established a synagogue, and built a whole colony based on slave labor.73 He crafted a little “Jewish homeland” on a large island in the Surinam River, which came to be known as the “Savannah of the Jews”.74 These settlers quickly acquired vast plantations producing sugar, coffee, cotton, and lumber, utilizing thousands of African slaves,75 as the indigenous population could not endure the forced labor and “died away rapidly.”76 By May 1667, records from the Thorarica region of Surinam indicated substantial Jewish landholdings:

[Thorarica] consisted of nine plantations for raising sugar cane with 233 slaves, 55 sugar kettles, 106 head of cattle, and 28 men plus an additional six plantations with 181 slaves, 39 sugar kettles, and 66 animals. All these plantations were owned by eighteen Portuguese Jews.77

By 1730, Surinam had reached its peak prosperity, boasting 400 plantations.78 Historical records from a 1707 slave auction in Surinam indicate that the ten largest Jewish buyers accounted for over 25 percent of the total amount spent. Caribbean Jews owned 115 plantations and played a significant role in the sugar export industry, which shipped 21,680,000 pounds of sugar to European and New World markets in 1730 alone. Furthermore, Jewish merchants from Newport and Charleston were heavily involved, with 120 out of 128 slave ships that docked in Charleston within a single year being undersigned by Jews from these cities.79

Excerpt from Alexander Falconbridge's 1788 Account of the Slave Trade:

“When the ships arrive in the West Indies, the slaves are disposed of, as I have before observed, by different methods. In general, they are purchased by Jews, upon speculation, at such a low price as five or six dollars a head. I was informed by a mulatto woman, that they purchased a sick slave at Grenada, upon speculation, for the small sum of one dollar!”80

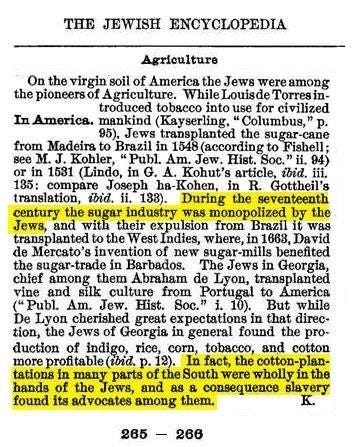

Even the Jewish Encyclopedia acknowledges that, during the seventeenth century, Jews monopolized the sugar industry and that cotton plantations in many parts of the South were entirely controlled by Jews.

Conclusion

This article draws extensively on the research presented in the excellent book “The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews: The Jewish Role in The Enslavement of the African” by the Nation of Islam. Additionally, the Nation of Islam's “Jews Selling Blacks: Slave Sale Advertising by American Jews” offers a significant compilation of historical advertisements from American newspapers, highlighting Jewish involvement in the buying, selling, and ownership of slaves. Readers interested in further exploring this subject are encouraged to read these works for a deeper understanding.

Finally, the inspiration for this article was the excellent book “The Jewish Onslaught” by Tony Martin, an academic and professor who has received multiple awards and honors from the American Philosophical Society. The book exposes the well-documented Jewish role in the Atlantic slave trade. In the link below, you can find a 2-hour lecture by Tony Martin about the Jewish role in the trading of African slaves:

Jewish Slave Trade Of Africans Historical Account By Prof. Tony Martin

“The Settlement of the Jews in North America” by Charles Patrick Daly p.80

“The Jews in Newport,” PAJHS, vol. 6 (1897)” by Max J. Kohler p.66

“Sins of the fathers: a study of the Atlantic slave traders, 1441-1807” by Pope-Hennessy, James. pp.240-241

“Zion in America: The Jewish Experience from Colonial Times to the Present” by Henry Feingold p.41

“Bittersweet Encounter: The Afro-American and the American Jew” by Robert G. Weisbord and Arthur Benjamin Stein, pp.23-24

“An Estimate and Analysis of the Jewish Population of the United States in 1790” by Ira Rosenwaike

“Some Aspects of the New York Jewish Merchant and Community, 1654-1820, PAJHS, vol. 66 (1976)” by Leo Hershkowitz pp.11,19

“The Jews in America: Four Centuries of an Uneasy Encounter: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989)” by Arthur Hertzberg p.25

“The History of Jews in America: From the Period of the Discovery of the New World to the Present Time” by Peter Wiernik p.52

“The Land That I Show You (New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978)” by Stanley Feldstein p.13

“Early American Jewry, Vol.1” (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1951) by Jacob Rader Marcus pp.64-65

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.2” (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.795

“Jewish Merchants in Colonial America (New York: Behrman’s Jewish Book House, 1939)” by Miriam K. Freund p.34

“Phases of Jewish Life in New York Before 1800, PAJHS, vol. 2 (1894)” by Max J. Kohler p.84

“Jewish Merchants in Colonial America” (New York: Behrman’s Jewish Book House, 1939) by Miriam K. Freund p.36

“The Jews of Virginia from the Earliest Times to the Close of the Eighteenth Century, PAJHS, vol. 20 (1911)” by Leon Hühner p.88

“Richmond’s Jewry 1769-1976” by Myron Berman p.159

“Early American Jewry, Vol.2” (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1951) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.188

“United States Jewry, 1776-1985, Volume 1” (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.211

“Richmond’s Jewry 1769-1976” by Myron Berman p.166

“The Jews of Charleston” (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1950) by Charles Reznikoff and Uriah Z. Engelman p.276 note 22

“Historia Judaica, vol. 13” (October 1951) p.160

“Essays in American Jewish History” (American Jewish Archives, KTAV Publishing House, 1975) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.275

“Jews of Georgia in Colonial Times, PAJHS, vol. 10 (1902)” by Leon Hühner p.66

“The Settlement of the Jews in Georgia, PAJHS, vol. 1 (1893)” by Charles C. Jones p.12

“The Jews of Georgia in Colonial Times, PAJHS, vol. 10 (1902)” by Leon Hühner pp.84-85

“Jews, Justice and Judaism” (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1969) by Robert St. John p.60

“Memoirs of American Jews 1775-1865, vol. 2” (New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1974) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.288

“Jewish Merchants in the Colonial Slave Trade, PAJHS, vol.34 (1938)” by Edward D. Coleman p.285

“The Jews of Georgia in Colonial Times, PAJHS, vol. 10 (1902)” by Leon Hühner p.87

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.366

“Memoirs of American Jews 1775-1865, vol. 2” (New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1974) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.297

“Memoirs of American Jews 1775-1865, vol. 2” (New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1974) by Jacob Rader Marcus p.324

“United States Jewry, 1776-1985, Volume 1” by Jacob Rader Marcus p.586

“Review of The Dutch in Brazil, 1624-1654, by C.R. Boxer, PAJHS, vol. 47, (1957-58)” by Herbert I. Bloom p.115

“The History of Jews in America: From the Period of the Discovery of the New World to the Present Time” by Peter Wiernik pp.29-30

“1732 and 1982 in Curaçao, AJHQ, vol. 72 (December 1982)” by Simeon J. Maslin p.159

“The Jews and Modern Capitalism” by Werner Sombart p.32

“Aspects of Jewish Economic History” by Marcus Arkin p.199

“Aspects of Jewish Economic History” by Marcus Arkin p.200

“Jews in Colonial Brazil” by Arnold Wiznitzer p.72-73

“Jews and Judaism in the United States: A documentary history” by Marc Lee Raphael p.14

“New World Jewry, 1493-1825, Requiem For The Forgotten” by Seymour B. Liebman p.145

“Phases of Jewish Life in New York Before 1800, PAJHS, vol. 2 (1894)” by Max J. Kohler p.95

“A History of the Marranos” by Cecil Roth p.292

“New World Jewry, 1493–1825: Requiem for the Forgotten” by Seymour B. Liebman p.179 & “1732 and 1982 in Curaçao, AJHQ, vol. 72 (December 1982)” by Simeon J. Maslin p.160

“Caribbean Project: Jews, Slavery, and the Dutch Caribbean” by Hunter Wallace

“The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its Peoples” by Stephan Palmié and Francisco A. Scarano

“History of the Jews of the Netherlands Antilles” by Isaac S. And Suzanne A. Emmanuel p.83

“Jews and Judaism in the United States: A documentary history” by Marc Lee Raphael p.24

“Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World” by Jonathan Schorsch p.176

“A Review of The Jewish Colonists in Barbados in the Year 1680” by Wilfred S. Samuel p.12

“A History of the Marranos” by Cecil Roth p.289

“Plantation Slavery in Barbados An Archaeological and Historical Investigation” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1978), by James S. Handler and Frederick W. Lange p.16

“Merchants and Jews: The Struggle for the British West Indian Caribbean, 1650-1750” (Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1984), by Stephen Alexander Fortune p.103

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” by Jacob Rader Marcus p.101

“The History of Jews in America: From the Period of the Discovery of the New World to the Present Time” by Peter Wiernik p.56

“A History of Barbados, 1625-1685” by Vincent T. Harlow p.265

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” by Jacob Rader Marcus p.114

“Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, 1689-1692” (1901), p.593

“The Jews and Modern Capitalism” by Werner Sombart p.36

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” by Jacob Rader Marcus pp.21-22

“Jewish Pioneers and Patriots” by Lee M. Friedman p.92

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” by Jacob Rader Marcus p.88

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” by Jacob Rader Marcus p.99

“A Successful Caribbean Restoration: The Nevis Story, AJHQ, vol. 61 (1971)”, by Malcolm Stern p.21

“The Nevis Story,” by Malcolm Stern p.23

“The History of the Jews of Philadelphia” (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1957), by Edwin Wolf and Maxwell Whiteman p.191

“The Colonial American Jew: 1492-1776, Vol.1” by Jacob Rader Marcus p.93

“The History of the Jews of Philadelphia” (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1957), by Edwin Wolf and Maxwell Whiteman pp.190-91

“The Jews in America: A History” (New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1972) by Rufus Learsi p.25

“Aspects of Jewish Economic History” by Marcus Arkin p.97

“Narrative of an Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (London, 1796; reprint, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1971)” by John Gabriel Stedman p.vii

“New World Jewry, 1493–1825: Requiem for the Forgotten” by Seymour B. Liebman p.186

“The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries” by Herbert I. Bloom p.157

“Pan-Africanism: Political Philosophy and Socio-Economic Anthropology for African Liberation and Governance Vol. 1” by Dr Fongot Kini-Yen Kinni p.99

“An account of the slave trade on the coast of Africa” by Alexander Falconbridge p.33

Fantastic research.

This is an excellent resource

Thank you